I, 1-4 “Introduction”

In nova fert animus mūtātās dīcere formās

corpora: dī, coeptīs (nam vōs mūtāstis et illās)

adspīrāte meīs prīmāque ab orīgine mundī

ad mea perpetuum dēdūcite tempora carmen.

Translation(*)

My soul inclines to speak of the transformation of forms into new bodies: o Gods, please assist my enterprise (in fact you have also transformed the forms) and keep on supporting my poem, from the first origin of the world up to my time.

Comment

Publius Ovidius Naso, which we will familiarly call Ovid, had a peculiar, unique characteristic of enormous value: he was a normal human being. He did not walk on the lakes, he did not resurrect dead, he did not separate the waters of the Tiber to let only the friends pass and slaughter the enemy; in short, he did not miracles. Ovid was one of us. He married three times, so we imagine him in his daily life, while he unravels and builds relationships. He fell into disgrace at the court and was sent into exile. His spicy work “Ars Amatoria” is an apology of betrayal and useful handbook for seduction in public places. I imagine he would have been a great companion of adventures, a pleasant evening guest. In summary, Ovid is not the typical prophet who screams in the desert, but a nice poet, able to enjoy the pleasures of life and at the same time to face and meditate on the deep and complex issues of the Metamorphoses.

The Metamorphoses are not a sacred text, but a poem where the author asks from the first verses aids to the Gods (Dī, adspīrāte et dēdūcite) to draw up his work. His request for help has a rational basis, in fact, it is the Gods themselves who have “transformed” the forms into bodies, so who could better help to understand what and how it happened?

In the paradigm of classical polytheism there are no creators, but gods that transform reality. I do not think it is a coincidence that we are talking about the transformation (or change) of the forms, the metamorphosis, (mūtātās formās in nova corpora) according to what was accepted not only by the Neoplatonic philosophers but by much of the culture of the time. The Demiurge is the author of the cosmos (κόσμος also means “order” in Greek), not the creator.

The question answered by Ovid is not “who created the world”, but:

How have the Gods shaped the world, from the origins of the universe to today, from (eternal) forms to the sensitive and changing plane?

I, 5-12 “il Caos”

5. Ante mare et terrās et, quod tegit omnia caelum

ūnus erat tōtō nātūrae vultus in orbe,

quem dixēre Chaos, rudis indīgestaque mōles

nec quicquam nisi pondus iners congestaque eōdem

non bene iunctārum discordia sēmina rērum.

10. Nullus adhūc mundō praebēbat lūmina Tītan,

nec nova crescendō reparābat cornua Phoebē,

nec circumfusō pendēbat in āëre tellūs

ponderibus lībrāta suīs, nec bracchia longō

margine terrārum porrexerat Amphītrītē,

15. utque erat et tellūs illīc et pontus et āër,

sīc erat instabilis tellūs, innābilis unda,

lūcis egens āër: nullī sua forma manēbat,

obstābatque aliīs aliud, quia corpore in ūnō

frīgida pugnābant calidīs, ūmentia siccīs,

20. mollia cum dūrīs, sine pondere habentia pondus.

Translation

Before the sea and the land and the sky, which covers everything, in nature there was only one aspect in all, which they called Chaos, a rough and disordered mass, nothing but an inactive agglomeration and at the same time a heap and a contrast of uncoordinated elements of the world.

The Titan still did not offer the lights to the world, nor did Phoebe regain new phases growing, nor did the earth hang in the diffused air, suspended on its weights, nor did Amphitrite stretch its arms over the long boundary of the emerged lands, and though there were earth and sea and air, the earth was unstable, the waves were not navigable, the air was without light: nothing was left in its form, one thing was opposing to another because in the same body the cold fought with the heat, the wet with the dry, the soft with the hard, the light with the heavy.

Comment

Chaos is the only primordial aspect before the Gods give shape to the world. Appearance, vultus, since it is the sensitive world not yet ordered by the forms. Its description as a material without form recalls the neo-Platonic matter, which was emanated according to Proclus directly from the One, and which has the characteristic of being able to accept the forms projected by the power transmitted by the higher entities. Philosophy has learned from mythology that Chaos is the first feature to appear in the formation of the cosmos, as an aspect, that is the material basis of the sensible world. Ovid, following this knowledge, starts his narration from the Chaos.

What is Chaos? We can perform a mental experiment. We take any object and place it on a table in front of us. Then mentally we eliminate all its qualities: color, consistency, perfume, form. What remains of it, in our representation, is a support to all the denied qualities, a shapeless something that exists only for its existence, as an empty container of quality. The qualities could stick for very short moments, making the shape completely unstable. It should be noted that Ovid’s vision is in contrast with that of certain modern magical movements that rely on the creative power of Chaos: according to the classical world Chaos is inert and passive (nec quicquam nisi pondus iners), receives only and does not generate anything, but it is the foundation of the world as it is a necessary condition and the Gods are those who shape it. It has neither unity nor division, it is an infinite multiplicity, united by the absence of discriminating attributes.

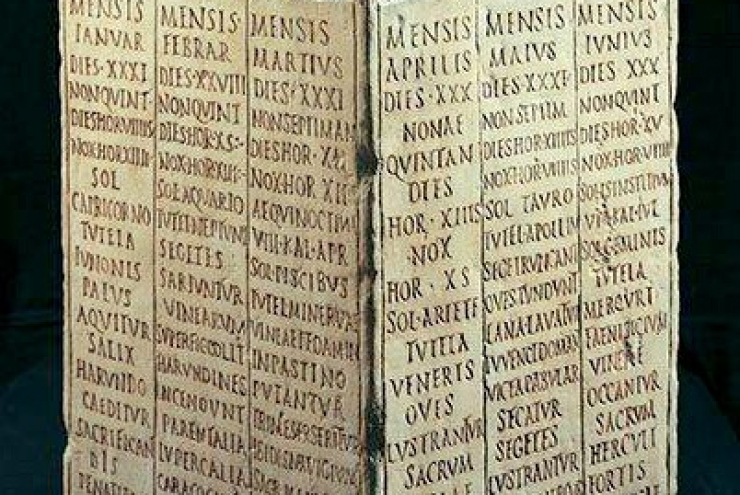

As a necessary condition, Chaos already contains the matter of the universe that is not yet ordered (utque erat et tellūs illīc et pontus et āër). Ovid explains that the order of the cosmos was still missing, beginning the poetic description in negative to make us imagine a world without first the Titan, the Sun, which we remember to be the metaphysical symbol of the One and therefore of the ordering principle. There follows the absence of Phoebe, the Moon, who presides over becoming, not as chaotic boiling, but as regular scans of time. The lunar phases are a regulatory change in terrestrial activities. The description ends with the absence of Amphitrite and its affectionate embrace, Neptune’s Nereid who represents the waters surrounding the emerged land. Her arms stretched towards the borders of the world have the reassuring action of delimiting the space of terrestrial activities: the feeling of the denied embrace communicates a great insecurity.

A world without light, without time, without space, where nothing remained in its form (nullī its form manēbat).

At this point, we, like the poet, need to reassure ourselves, to wake up from this chaotic nightmare. We look around. We see the space with its planets, the sky with its atmospheric phenomena, a solid earth under our feet, rivers and lakes, the sea populated with fish. Fortunately, a wonderful world surrounds us, with its laws and its natural order. The question is generated by itself, almost emerging from the same Chaos: how did we move from Chaos to the wonderful cosmos that surrounds us?

This will be discussed in the next article.

Mario Basile

Fori Hadriani scripsit, ad X Kal. Dec. MMDCCLXXI

(*) the translation of the Metamorphosis is by the author.